(Produkt nie został jeszcze oceniony)

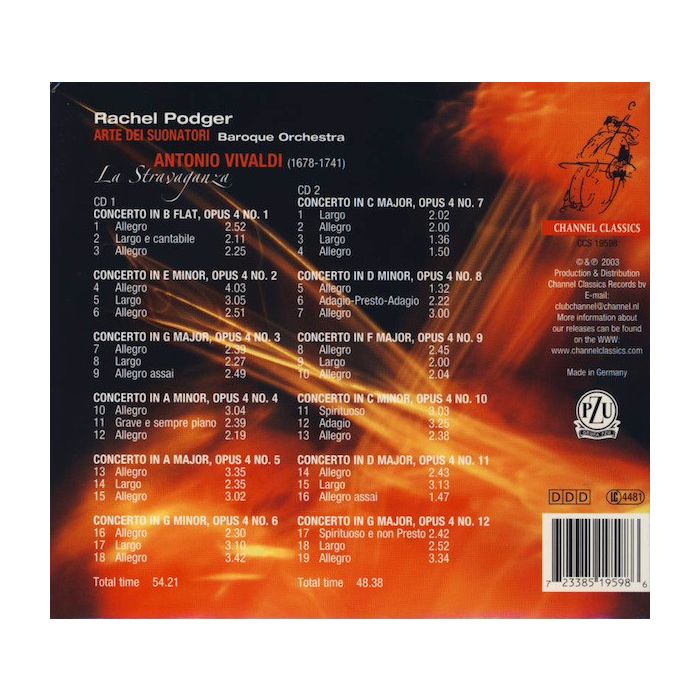

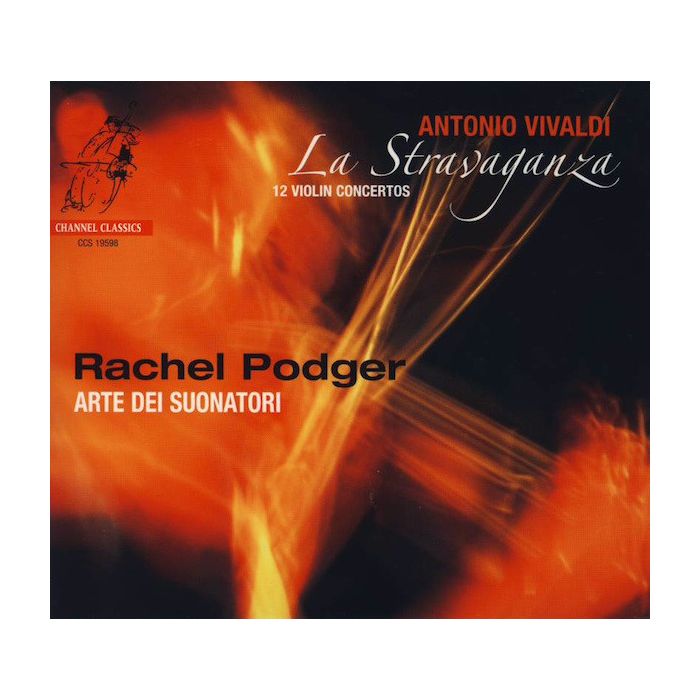

Vivaldi - La Stravaganza 12 Violin Concertos (2CD)

Immersing myself in the 12 Concertos of ‘La Stravaganza’ was an intense and exhilarating experience, and one which has left me full of wonder at Vivaldi’s seemingly endless capacity for invention. Having had many opportunities to get to know his music ever since I started playing the violin (the well-loved A minor Concerto from L’estro Armonico is one of the set pieces in Suzuki’s violin method and played by most 6-10 year olds!), the Seasons and L’estro featuring strongly in baroque concert programmes, it was with interest but also a number of pre-conceptions that I approached these relatively obscure concertos. I rather arrogantly assumed I’d have to put my mind to making them sound as different from each other as possible, as they probably wouldn’t assert their own character within the set by themselves. I’m ashamed of that thought now, since I quickly realised that I wasn’t dealing with ‘samey’ music at all, but with extreme inventiveness within a definite framework. Vivaldi uses melodic figurations in somany remarkable ways. It’s as though he likes to experiment with every possible variant and push the players beyond expectation of what might be coming next. • Having said that, the most predictable comment about his music is that his music is predictable! But listen, for example, to the last movement of Concerto no.1, where we see him first setting up a simple phrase, experimenting with the opening figure (first 2 bars) in minimal ways, taking us unexpectedly (unpredictably!) into a new key just when we expect the solo part to take charge. For 111 bars he lets his imagination run riot with this very simple opening figure, transforming it and avoiding any obvious phrasing that the listener might assume. This way, he creates a wonderful spirit of exploration in the music. Fragments of figurations are often thrown from one part to the next in the orchestra, later making up a whole phrase. Vivaldi also uses very simple tools by, for instance, making the tune leap across the two violin parts: there is an ascending triadic figure which goes to-and-fro between the fiddles as a variation on a similar tune heard earlier in a single part within the orchestra (Concerto no.3, first movement). His citing of a tune, repeating it twice note-by-note and then changing it at the last minute is often both witty and clever (like in Concerto no.5, first movement, during the 4th tutti section). • Vivaldi conveys so much variety and character; it feels easy to perform as the language is so direct and the expression within looks candidly at you from the page. The sublime slow movements (such as in Concertos nos. 1 and 11) recall descriptions or paintings of paradise where you literally feel like you’re hovering on a cloud for the duration of the movement… and the demon-like moments in Concerto no.8 (first movement) make you believe you’re being devoured by hungry tigers. I want to thank all the members of Arte dei Suonatori for helping to make this recording such an exciting project and for being so good-natured in putting up with all my experiments in the sessions. And I’d like to thank Jared Sacks, Jonathan Freeman-Attwood, Cezary Zych and Tim Cronin without whom this recording would not have been possible.

Diapason d’Or

Gramophone: 'Best Baroque Recording of the year' (2003)

Gramophone: 'Editor´s Choice'

Produkt dostępny.

Wysyłka w ciągu 3 dni roboczych

Darmowa wysyłka dla zamówień powyżej 300 zł!

Darmowy kurier dla zamówień powyżej 500 zł!

sprawdź koszty wysyłki