(Produkt nie został jeszcze oceniony)

kompozytor

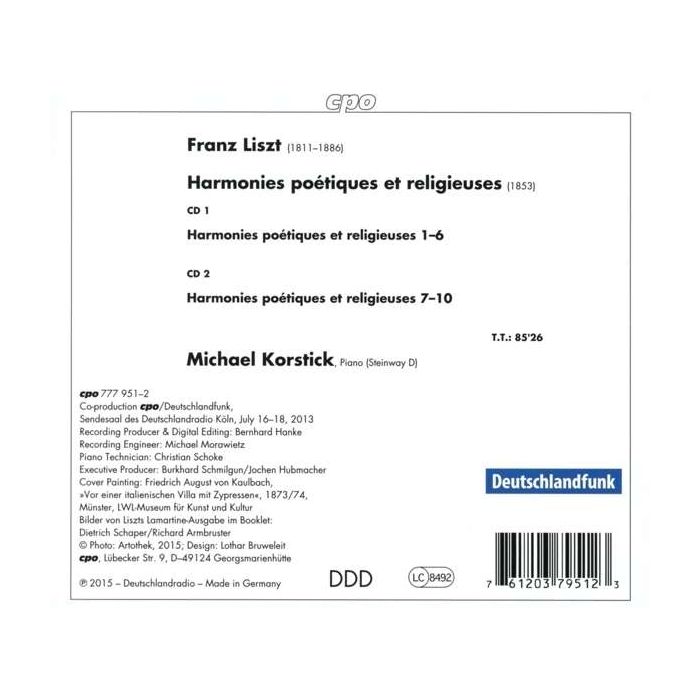

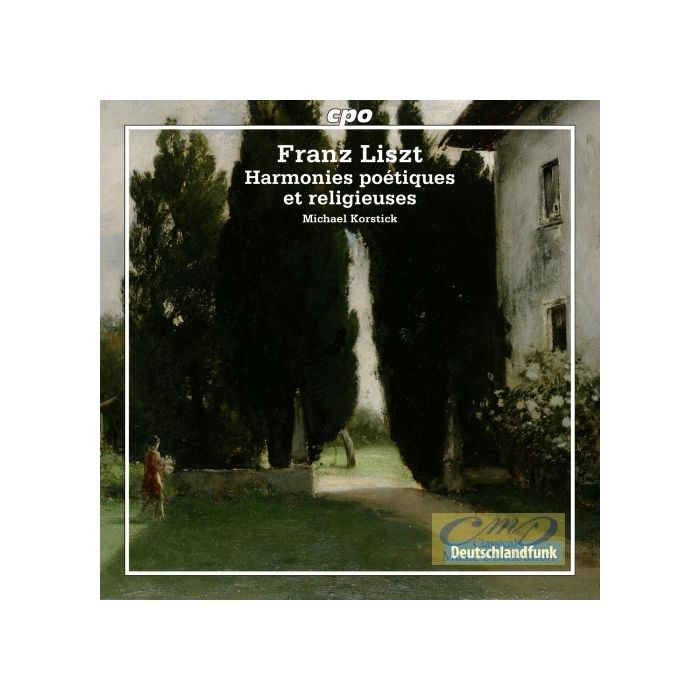

Liszt, Franz

tytuł

Liszt: Harmonies poétiques et religieuses

wykonawcy

Korstick, Michael

nr katalogowy

CPO 777 951-2

opis

The ten pieces which form the Harmonies Poétiques et Réligieuses were composed by Liszt between 1845 and 1852, and are an expression of the composer’s devotion to Catholicism. In 1848 he abandoned his career as a travelling virtuoso and settled in Weimar with his companion Princess Carolyn von Sayn-Wittgenstein, fulfilling a long-standing invitation to work as Kapellmeister, dating back to 1842, from the Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna of Russia. He remained in this post for thirteen years, until 1861. It was a fruitful period, with many important works being written, among them this cycle. It is made up of religiously inspired pieces most, but not all, based on the poetry of Alphonse de Lamartine, and dedicated to Princess Carolyn. Throughout the cycle’s lengthy gestation period, Liszt incorporated some earlier material. Many times the pieces have been both performed and recorded in isolation, especially Funérailles and the Bénédiction de Dieu dans la solitude. The ten-piece collection seems to be rarely programmed, and the catalogue is far from inundated with complete cycles. This is a pity, as there are many treasures lying within: Invocation, Pensée des morts, Andante lagrimoso and Cantique d’amour. In the Liszt oeuvre, they are compositionally advanced, with some bold innovative harmonies. The Pensée des morts, Funérailles, and the Andante lagrimoso are harmonically stark, sober and restrained, presaging the understated late piano works. The two most well-known pieces of the set are the Bénédiction de Dieu dans la solitude and Funérailles. The Bénédiction for me is the finest and one of the most beautiful piano works ever penned. There are several outstanding recordings including those by Steven Osborne and Stephen Hough. However, it is the Philips’ recording by Alfred Brendel that, in my opinion, has never been matched. The left hand melody at the beginning of the work sounds a little earthbound in Korstick’s performance, and the right–hand accompanying figurations lack the lightness and diaphanous quality Brendel brings to them. Korstick’s Funérailles fares much better and he negotiates the varying moods and contours of the narrative with imagination and skill. The dark, sombre opening contrasts with the more lyrical section in the middle. At the end he unleashes some powerful passion and drama. Pensée des morts is a magnificent work, rarely performed, and it’s difficult to see why. I love the live performance from Moscow given by Richter, which I reviewed recently (Philips Presto CD 4321422), even though the Russian takes an extra three minutes more than Korstick, Osborne and Brendel. Korstick’s reading displays many of Richter’s endearing qualities including profundity, an expression of deep sorrow and spirituality, yet without ever sounding mawkish. His Ave Maria has a devotional simplicity, whilst the Cantique d’amour is passionate and ecstatic. CPO’s annotations are excellent, providing useful background. However, the recording engineers have done Michael Korstick no favours. The pianist is too closely miked, resulting in an uncomfortable ‘in your face’ feeling. This renders the piano sound harsh and strident in loud passages, of which there are many, with some musical detail obscured. This is compounded by the fact that the acoustic of the Sendesaal des Deutschlandradio is much too resonant. For my money, I have to go with Steven Osborne’s cycle on Hyperion, superbly recorded with warmth and intimacy.

nośnik

CD

data wydania

7.10.2015

EAN / kod kreskowy

761203795123

58,00 zł

Produkt na zamówienie

Wysyłka ustalana indywidualnie.

Darmowa wysyłka dla zamówień powyżej 300 zł!

Darmowy kurier dla zamówień powyżej 500 zł!

sprawdź koszty wysyłkiProduktu jeszcze nie zrecenzowano, chcesz być pierwszy?

Pozostałe płyty tego wykonawcy

1 / 6