(Produkt nie został jeszcze oceniony)

kompozytor

różni kompozytorzy

tytuł

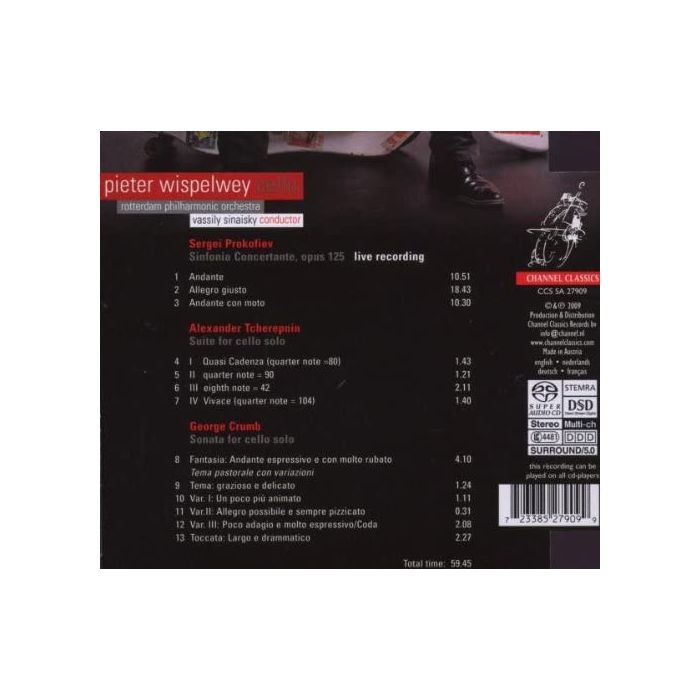

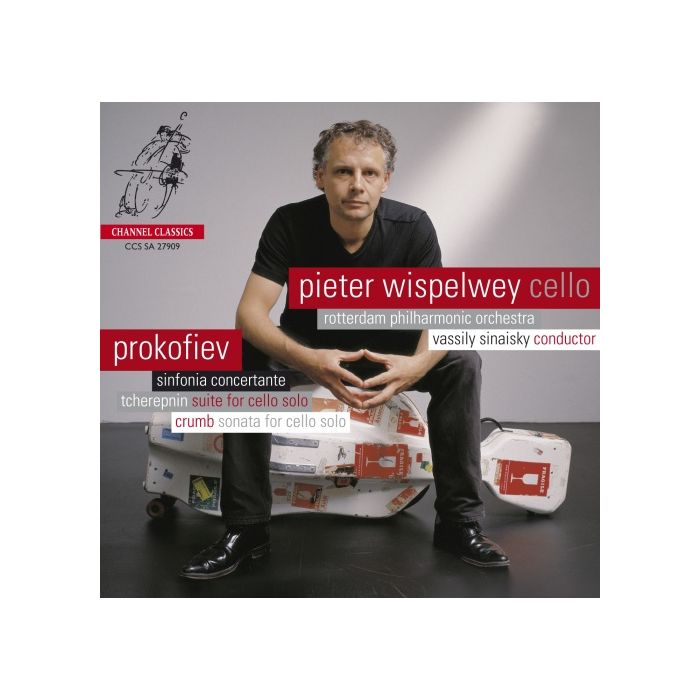

Prokofiev: Sinfonia Concertante, TCHEREPNIN: Suite for cello solo, CRUMB: Sonata for cello solo

pełny spis kompozytorów

Crumb, George, Prokofiev, Sergey, Tcherepnin, Alexander

wykonawcy

Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra, Sinaisky, Vassily, Wispelwey, Pieter

nr katalogowy

CCS SA 27909

opis

Prokofiev was a musical polyglot and chameleon and his Sinfonia Concertante is a continent without borders, a journey through style, language, time and tradition, like a postmodernist statement avant la lettre. A more than thorough reworking of a Thirties cello concerto became a postwar Cyclopean piece full of contrasts: dark and light, animalistic and ethereal, cruel and tender, serious and sardonic, rugged and sophisticated, a feast to play and an orgy to witness. The three movements are spectacularly diverse. An atavistic opening movement is followed by a second movement that starts off as a concerto allegro, but then keeps expanding, practically into a concerto by itself, with an abundance of all kinds of neo-classical, anarchistic and ‘danse macabre’ elements, with elaborate, utterly expressive lyrical episodes and of course that outrageous cadenza. The third movement is a mixture of the pompous, the absurdist and the capricious. Something like a theme and variations set up is interrupted by a string of little dances with references to Mahler and Kurt Weill. The main theme returns in a mighty tutti version and after two further, more atmospheric and alienating variations, the movement works its way towards some sort of a threefold final climax, consisting of an orchestral cataclysm in combination with a soloist delirium. In other words lots of Twenties, Thirties, lots of nineteenth century, Mongolia, Asia, Middle Europe, Slava, Stalin, euphoria, psychosis and beauty. Too much to mention. The attraction for cellists lies in the phenomenal technical challenge, the lyrical intensity and the many different roles the soloist, as the main character in this epic, has to play. A great fighting spirit is asked for. If things go well and the dragon is down at the end, the satisfaction is enormous. Besides, who wouldn’t want to be Slava for forty minutes? The presence and inspiration of the big man is all over the piece. For this live recording, to have the support of Vassily Sinaisky and this orchestra, that has a decade of Gergiev behind it, was a tremendous privilege. They were exciting days. The choice for the two solo encores, Tcherepnin and Crumb was made to give two examples on a totally different scale from the same early postwar years in which the Concertante was written. The Tcherepnin particularly, is almost on a miniaturist scale. Pieter Wispelwey

nośnik

CD, SACD x 1

wydawca

Channel Classics

data wydania

25.08.2009

EAN / kod kreskowy

723385279099

89,00 zł

Produkt na zamówienie

Wysyłka ustalana indywidualnie.

Darmowa wysyłka dla zamówień powyżej 300 zł!

Darmowy kurier dla zamówień powyżej 500 zł!

sprawdź koszty wysyłki