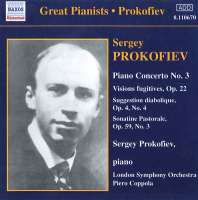

kompozytor

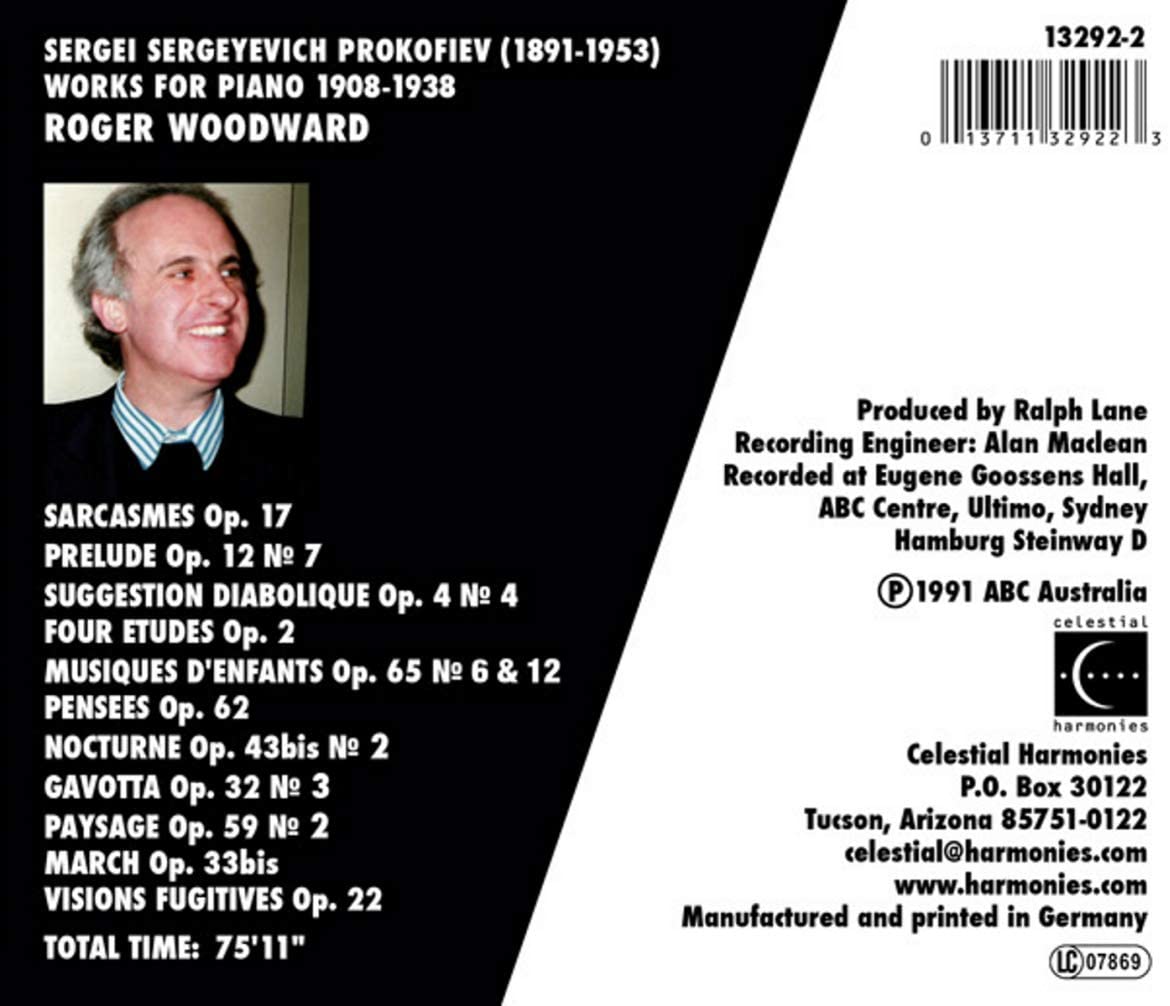

Prokofiev, Sergey

tytuł

Prokofiev: Works for Piano

wykonawcy

Woodward, Roger

nr katalogowy

13292-2

opis

Woodward's musical universe revolves around a number of centers which sometimes appear concentric: there is the French school, dominated by Chopin and Debussy. J.S. Bach occupies a special galaxy with the two books of The Well–Tempered Clavier, the Fantasia & Fugue BWV 903 and the Partitas nos. 2 and 6. There is the Western avant-garde, from Barraqué to Xenakis, and from Hans Otte to P. M. Hamel and Takemitsu. And then there is the Russian sphere which now is represented in three releases on Celestial Harmonies, spanning almost four decades, biographical for the composers, autobiographical for the musician. The Shostakovich 24 Preludes and Fugues were recorded in London in the summer of 1975, just a little over a month before the composer's death; Prokofiev's Works for Piano 1908–1938 was recorded in Sydney in 1991; and, finally, Music of the Russian Avant–Garde 1905–1926 that was recorded in Bavaria, near Munich in 2009. The artistically, politically and socially fascinating period of transition from Tsarist Russia to the Soviet Union under Stalin is the source of the works on Music of the Russian Avant–Garde (1905-1926), a review of little–known compositions that Woodward had kept in mind since his student days in Warsaw in the mid '60s. At that time, he succeeded in obtaining access to rare works, some thought to have been lost, from the hands of Lina Prokofieva, Prokofiev's widow, and some found in Polish radio archives. Woodward's recording of the Shostakovich Preludes and Fugues―the first of the complete cycle outside the Soviet Union at the time―connects with Bach's Well-Tempered Clavier which we know was Shostakovich's inspiration after he had visited East Germany in 1950 on the occasion of the 200th anniversary of Bach's death. Woodward experienced history in reverse, considering that he recorded Shostakovich's Op. 87 twenty–five years before recording The Well–Tempered Clavier. Still, one cannot listen to one without hearing the other shining through. The Prokofiev recording stems from 1991, made on the occasion of the composer's centenary. Woodward had heard Sviatoslav Richter play Prokofiev a number of times during his studies in Warsaw, and his friendship with Lina Prokofieva gave him additional insight into how to approach the music. Woodward had become increasingly fascinated with Prokofiev's complex dichotomies; he writes that contrasting characteristics emerged from a tumultuous first period which took root and dominated a lifetime's artistic growth that might be described as both abrasive and lyrical. The first is characterised by percussive, motoric rhythms and dissonant harmonies evident in piano pieces such as Sarcasmes (1912). The second style is totally different and more evident in the neoclassic charm of the C-major Prelude Op. 12. Prokofiev′s cycle Visions Fugitives—its twenty parts not often heard complete—concludes the recording. Both of Prokofiev's characteristics are represented to good measure; the work symbolizes the transition into the modern world of the 20th century without disconnecting from the past, and it also guides effortlessly, following common practice at the time as heard in Debussy or Bartók, on a journey between different musical worlds.

nośnik

CD

gatunek

Muzyka klasyczna

producent

Celestial Harmonies

data wydania

26-09-2012

EAN / kod kreskowy

13711329223

Produkt nagrodzony:

MusicWeb International: 'Recording of the Month' (2013)

(Produkt nie został jeszcze oceniony)

cena 64,00 zł

lubProdukt na zamówienie

Wysyłka ustalana indywidualnie.

Darmowa wysyłka dla zamówień powyżej 300 zł!

Darmowy kurier dla zamówień powyżej 500 zł!

sprawdź koszty wysyłki