kompozytor

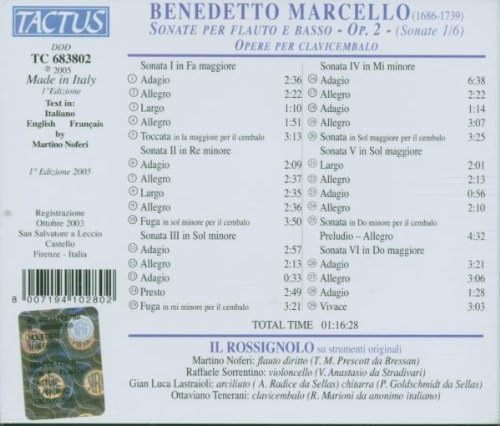

Marcello, Benedetto

tytuł

Marcello: Sonate per Flauto e Basso, Op. 2

wykonawcy

Il Rossignolo;

Noferi, Martino;

Tenerani, Ottaviano

Noferi, Martino;

Tenerani, Ottaviano

nr katalogowy

TC 683802

opis

From his early works (including the sonatas on this CD) to his last cantatas, Benedetto Marcello's compositions became increasingly complex, both in terms of form and the number of voices for which he wrote.

It can be said that he was instrumental in the transition from the "prima prattica" to the "seconda prattica", i.e. that he moved in the direction of clearer emotions and rhetoric, but remained firmly connected to the strict early counterpoint.

It was the quality of both innovation and respect for past practice that won him praise for his psalms from some of the greatest composers of the time: Johann Mattheson, who appreciated the fact that there were not "troppe voci differenti, e contrappunti troppo affaticati e sforzati" (too many different voices and too much tiring and artificial counterpoint), and Giovanni Bononcini, Domenico Sarri, Francesco Gasparini and Georg Philipp Telemann, who also expressed their appreciation.

And it was precisely this quality that led later generations to regard Benedetto Marcello and Handel as forerunners of Gluck's 'sublime' style. We believe that this mixture of 'affection' and rigor has led some to believe that the sonatas recorded here are overly simple. This opinion is related to the fact that the "Suonate a flauto solo... opera seconda" are early works, so they are wonderfully simple and at first glance seem to lack substance.

Very good examples of this are the theme from A Tempo Giusto Vivace in Sonata VI, which is reminiscent of a nursery rhyme or children playing in the calli in Venice; or that from the first Allegro from Sonata I in F major, which is barely uttered as it becomes familiar and vies for our attention. Then there are the frequent Gigues in 12/8 time (the second Allegro in Sonatas I and V in this first volume), the Sarabandes and their imitations, the Passepied in 3/8 time (the last Allegro in Sonata IV or the concluding Presto A Tempo Giusto in Sonata III, whose rhythm gave us particular pleasure) and the Siciliane (also in 12/8 time).

In the slow three-part movements (such as the Largo in Sonata II, the second Adagio in Sonata III or the Largo in Sonata V), the melodic pattern remains unadorned (we knew how to vary it: the slow movements from Archangelo Corelli's Opera V in the edition published by Roger are good examples, although they are not in ritornello form), but they are full of natural melodies and fresh phrasing, and the first slow binary movements (in 4/4 time, which Quantz calls a "flattering supplication") are characterized by a powerful ascending melody.

• Marcello, B: Fuga in E minor

• Marcello, B: Sonata for flute and organ in B minor, Op. 3 No. 2

• Marcello, B: Sonata for Recorder and Continuo in C major, Op. 2 No. 6

• Marcello, B: Sonata for Recorder and Continuo in D minor, Op. 2, No. 2

• Marcello, B: Sonata for Recorder and Continuo in E minor, Op. 2 No. 4

• Marcello, B: Sonata for Recorder and Continuo in F major, Op. 2, No. 1

• Marcello, B: Sonata for Recorder and Continuo in G major, Op. 2, No. 5

• Marcello, B: Sonata for Recorder and Continuo in G minor, Op. 2 No. 3

• Marcello, B: Sonata in D minor Op. 2 No. 2

It can be said that he was instrumental in the transition from the "prima prattica" to the "seconda prattica", i.e. that he moved in the direction of clearer emotions and rhetoric, but remained firmly connected to the strict early counterpoint.

It was the quality of both innovation and respect for past practice that won him praise for his psalms from some of the greatest composers of the time: Johann Mattheson, who appreciated the fact that there were not "troppe voci differenti, e contrappunti troppo affaticati e sforzati" (too many different voices and too much tiring and artificial counterpoint), and Giovanni Bononcini, Domenico Sarri, Francesco Gasparini and Georg Philipp Telemann, who also expressed their appreciation.

And it was precisely this quality that led later generations to regard Benedetto Marcello and Handel as forerunners of Gluck's 'sublime' style. We believe that this mixture of 'affection' and rigor has led some to believe that the sonatas recorded here are overly simple. This opinion is related to the fact that the "Suonate a flauto solo... opera seconda" are early works, so they are wonderfully simple and at first glance seem to lack substance.

On the contrary, we believe that it is the flexibility that is so readily apparent in some of the themes that makes these easily recognizable and familiar compositions unique and poignant.

Very good examples of this are the theme from A Tempo Giusto Vivace in Sonata VI, which is reminiscent of a nursery rhyme or children playing in the calli in Venice; or that from the first Allegro from Sonata I in F major, which is barely uttered as it becomes familiar and vies for our attention. Then there are the frequent Gigues in 12/8 time (the second Allegro in Sonatas I and V in this first volume), the Sarabandes and their imitations, the Passepied in 3/8 time (the last Allegro in Sonata IV or the concluding Presto A Tempo Giusto in Sonata III, whose rhythm gave us particular pleasure) and the Siciliane (also in 12/8 time).

In the slow three-part movements (such as the Largo in Sonata II, the second Adagio in Sonata III or the Largo in Sonata V), the melodic pattern remains unadorned (we knew how to vary it: the slow movements from Archangelo Corelli's Opera V in the edition published by Roger are good examples, although they are not in ritornello form), but they are full of natural melodies and fresh phrasing, and the first slow binary movements (in 4/4 time, which Quantz calls a "flattering supplication") are characterized by a powerful ascending melody.

Works:

•Marcello, B: Flute Sonata in F major, Op. 2, No. 1

• Marcello, B: Fuga in E minor

• Marcello, B: Sonata for flute and organ in B minor, Op. 3 No. 2

• Marcello, B: Sonata for Recorder and Continuo in C major, Op. 2 No. 6

• Marcello, B: Sonata for Recorder and Continuo in D minor, Op. 2, No. 2

• Marcello, B: Sonata for Recorder and Continuo in E minor, Op. 2 No. 4

• Marcello, B: Sonata for Recorder and Continuo in F major, Op. 2, No. 1

• Marcello, B: Sonata for Recorder and Continuo in G major, Op. 2, No. 5

• Marcello, B: Sonata for Recorder and Continuo in G minor, Op. 2 No. 3

• Marcello, B: Sonata in D minor Op. 2 No. 2

nośnik

CD

gatunek

Muzyka klasyczna

producent

Tactus

data wydania

11-11-2005

EAN / kod kreskowy

8007194102802

(Produkt nie został jeszcze oceniony)

cena 58,00 zł

lubProdukt dostepny w niewielkiej ilości.

Wysyłka w ciągu 3 dni roboczych

Darmowa wysyłka dla zamówień powyżej 300 zł!

Darmowy kurier dla zamówień powyżej 500 zł!

sprawdź koszty wysyłki