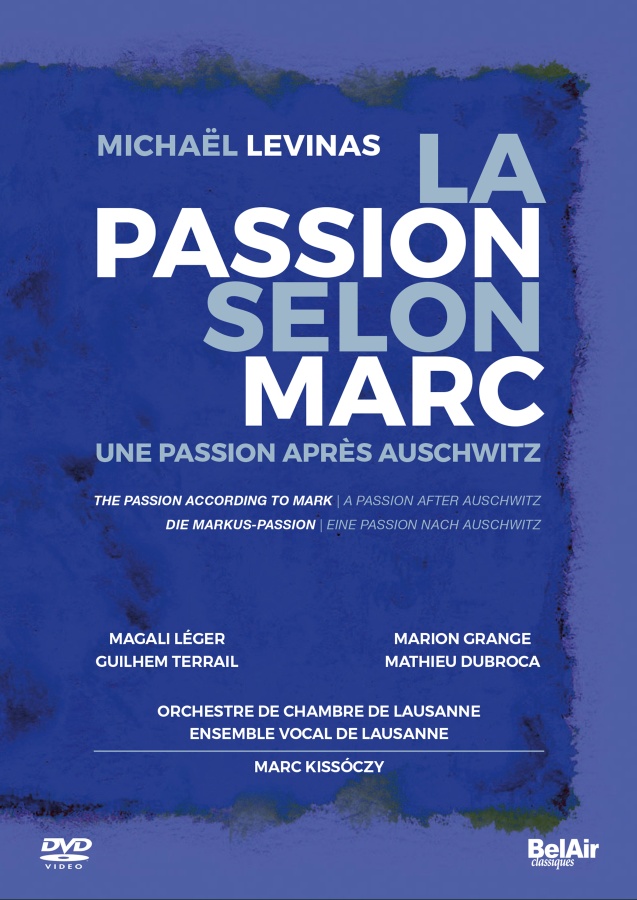

kompozytor

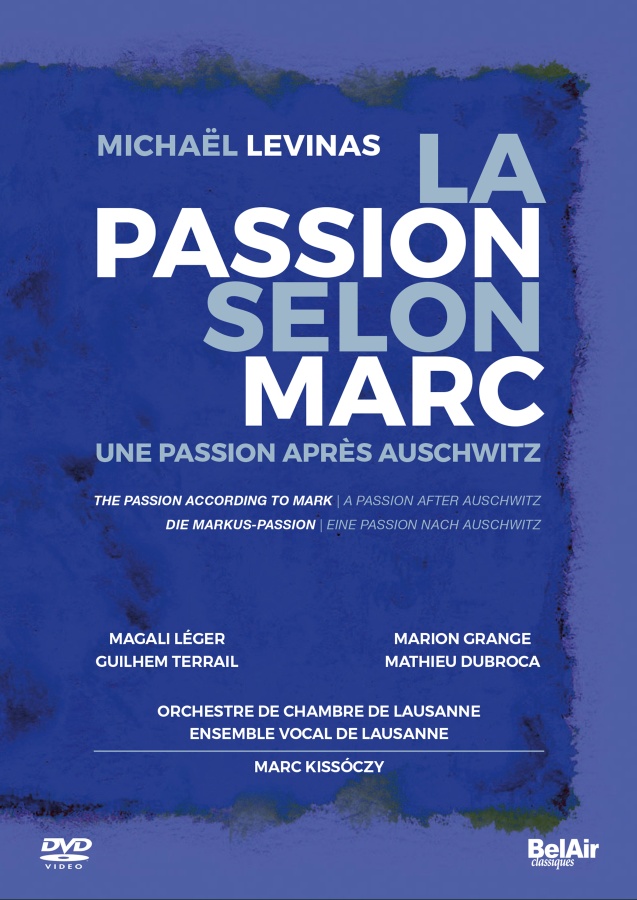

Levinas, Michaël

tytuł

Levinas: La Passion selon Marc

wykonawcy

Orchestre de Chambre de Lausanne;

Kissoczy, Marc

Kissoczy, Marc

nr katalogowy

BAC 152

opis

Texts: Gospel of Mark after the French Bible from the 13th century, transcribed by Michel Zink • Excerpts from the Mystère de la Passion by Arnoul Gréban (1452), Jewish prayers (‘Hatzi Kaddish & El male Rahamim), Paul Celan’s poems (Die Schleuse & Espenbaum) • With: Magali Léger (soprano) • Marion Grange (soprano) • Guilhem Terrail (counter-tenor) • Mathieu Dubroca (baritone) • Marie Hamard (mezzo-soprano) • Tristan Blanchet (tenor) • Simon Savoy (counter-tenor) • Ensemble vocal de Lausanne • La Passion selon Marc. Une Passion après Auschwitz (The Passion According to Mark. A Passion after Auschwitz), premiered in April 2017. The project was commissioned to French composer Michaël Levinas by the Swiss association «Musique for a present time», as part of the events commemorating the 500th anniversary of Luther’s reform. This original oratorio is not only a reinterpretation or a mere revisitation of the Passion - what the many references to Bach’s Passions could lead to believe, it painfully faces, indeed, the irreconciliable nature of the Passion and the Holocaust. • What is the object of this Passion after Auschwitz, which revolves around what can link two musical traditions, two religions that have been separated by barbarism. Which music, which tradition, which language can the composer use in order to express this double silence, both historical and theological, both human and divine ? It is no coincidence that Levinas chose to start his score with a quote by his father, philosopher Emmanuel Levinas, from his book Otherwise than being and beyond essence : so he could pay tribute to the «six million people who were murdered by the Nazis», but also to the «millions of human beings all over the world, regardless of their origin or religion, who suffer from the same hatred of the other, of the same antisemitism.» • «After the Holocaust, is it possible to compose without crying and trembling ?», Michaël Levinas asks. It is not about anger or compassion. Because of the subtle polyphonies written for the chorus, the voices and the orchestra, and also because of the way the different languages (Old French, Yiddish, Aramaic, German) create meaning out of one another, both the structure and the musical language of this Passion are incredibly intricate. But they are so for a reason : by putting side by side western musical traditions and the tragic component of modern history, Levinas manages to «shake», during the artistic process, the future of the Holy Language and of the Gospel after Auschwitz. What separates therefore the Gospel of Mark from the Jewish prayer for the dead (Kaddish) or from the El male Rahamim, or from the two poems by Paul Celan ending the work, is not so much a question of representation, but more accurately it is a way to make the tragedy resound, without any artifice and without any safety net.

nośnik

DVD

gatunek

Muzyka klasyczna

producent

Bel Air Classiques

data wydania

06-05-2019

EAN / kod kreskowy

3760115301528

(Produkt nie został jeszcze oceniony)

cena 99,00 zł

lubProdukt na zamówienie

Wysyłka ustalana indywidualnie.

Darmowa wysyłka dla zamówień powyżej 300 zł!

Darmowy kurier dla zamówień powyżej 500 zł!

sprawdź koszty wysyłki