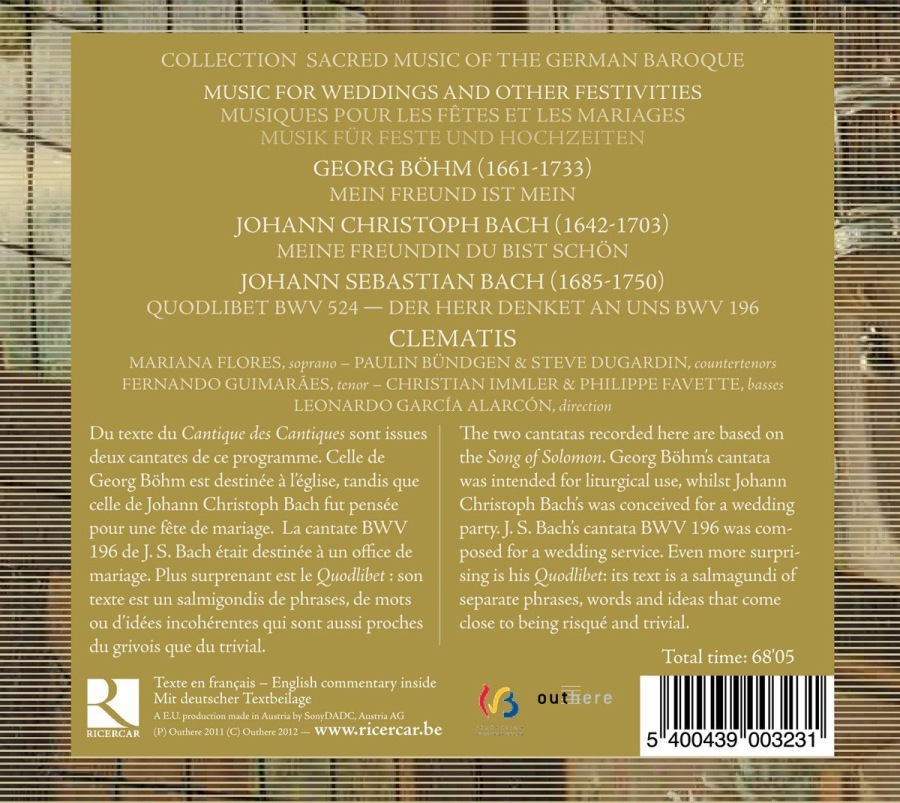

kompozytor

Bach, Johann Sebastian;

Böhm, Georg;

Bach, Johann Christoph

tytuł

Bach; J.C. Bach; Böhm: Music for Weddings and other festivities

wykonawcy

Clematis;

Garcia Alarcón, Leonardo

Garcia Alarcón, Leonardo

nr katalogowy

RIC 323

opis

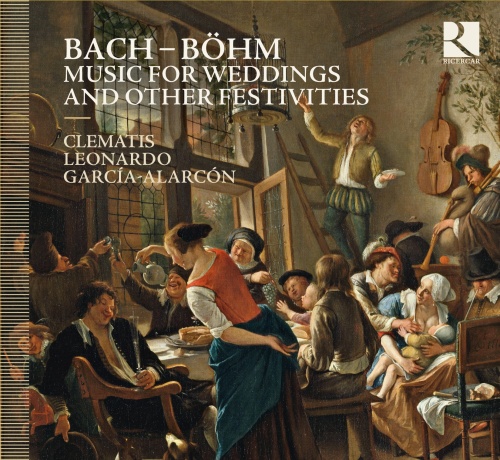

Let us once more immerse ourselves in the musical life of Eisenach as it was at the end of the 1670s. One Sunday afternoon, after having played for the services in their respective churches, the cousins Johann Ambrosius Bach and Johann Christoph Bach were sitting in a Bierstube, each with a mug of beer and a meerschaum pipe. A moment of relaxation, with word games, laughter and a discussion about Johann Christoph’s coming marriage. There would naturally be music for the wedding, with a cantata for the church service at the very least. That particular Sunday morning’s cantata had been based on texts from the Song of Solomon — not Böhm’s, of course, because Böhm had only been born in 1661. The sensual and at times erotic flavour of the words amuses them and, after several beers and pipefuls of tobacco, they have an idea for a secular cantata for the festivities that will follow the wedding ceremony. Christoph will compose the music, whilst Ambrosius will put together the text and instructions for its performance. Even though we do not know how this cantata was performed, its score has survived complete with all of its the puzzles and riddles. • The sublime chaconne in which the beloved proclaims her love and in which the violin line (as demanded by Ambrosius) symbolises her dreams and desires is both sensual and strong, the image of love itself and its blend of tenderness and strength: it is indeed a love scene. The two other sections are more theatrical in character: an introduction in dialogue form that describes the clandestine meetings of the lovers and a finale that is an open invitation to the festivities and to the food and drink that will be served. But how can we convey something of the atmosphere of such festivities? It is difficult to imagine a performance that is based on the text alone. The musicians of the Clematis seize the opportunity to get into the spirit of the occasion: halfway through the wedding breakfast they get out their instruments, push the tables together and share the scores that have been placed wherever there is room — on the edge of a table, on a chair — and the party begins with Esset und trinket. The wine, however, has been flowing for some time and the tempi get slower... All of the above is of course accompanied by unceasing thanks to God for his gift of life! Johann Sebastian Bach must have heard talk of such festivities and their celebratory cantatas (the scores of which he knew) from his early childhood. It must have been very much in the same spirit that he was inspired to compose, heaven only knows for what occasion, the incredible Quodlibet that seems to be so out of place amongst all his other works. If, however we carefully examine how Bach composed his secular (and even a few sacred) cantatas, we can see that he had a great instinct for theatre and for amusement. Certain passages in his biography even reveal that he was not a man who would turn down a good glass of wine!

nośnik

CD

gatunek

Muzyka klasyczna

producent

Ricercar

data wydania

23-05-2012

EAN / kod kreskowy

5400439003231

Produkt nagrodzony:

ICMA 'Nominee' (2012)

(Produkt nie został jeszcze oceniony)

cena 79,00 zł

lubProdukt dostepny w niewielkiej ilości.

Wysyłka w ciągu 3 dni roboczych

Darmowa wysyłka dla zamówień powyżej 300 zł!

Darmowy kurier dla zamówień powyżej 500 zł!

sprawdź koszty wysyłki