kompozytor

różni kompozytorzy

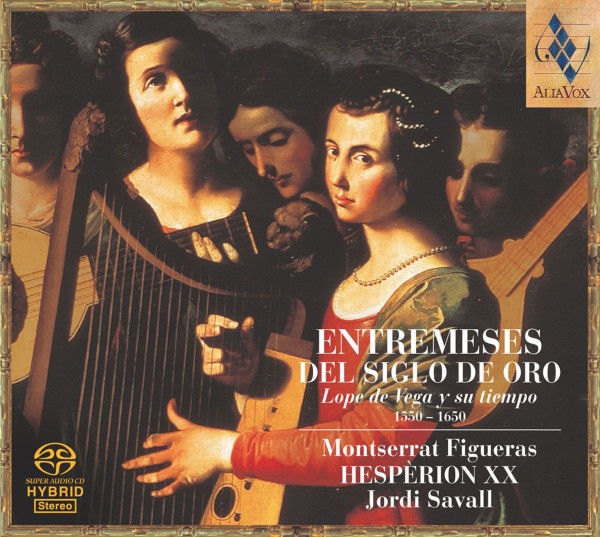

tytuł

Entremeses del siglo de oro - Lope de Vega

pełny spis kompozytorów

Ortiz, Diego;

Cabezon, Antonio de;

Castro, Francisco José de;

Vásquez, Juan;

Machado, Manuel;

Vega, Lope de

Cabezon, Antonio de;

Castro, Francisco José de;

Vásquez, Juan;

Machado, Manuel;

Vega, Lope de

wykonawcy

Savall, Jordi;

Figueras, Montserrat;

Hespèrion XX

Figueras, Montserrat;

Hespèrion XX

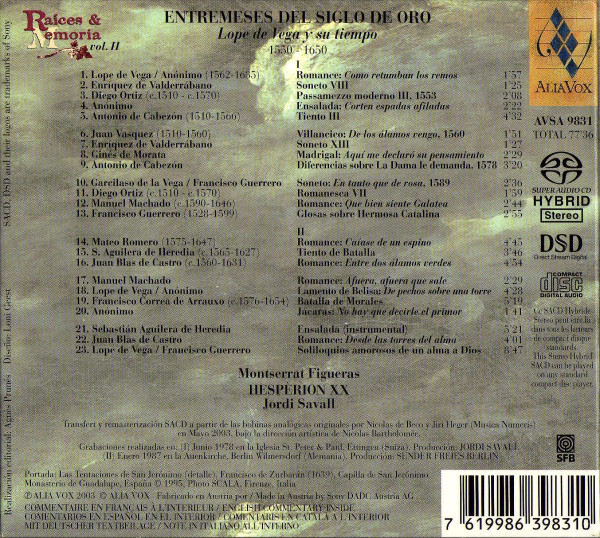

nr katalogowy

AVSA 9831

opis

The belated re-emergence from the mists of the past of the Spanish poet and dramatist Lope Felix de Vega Carpio should serve to increase our awareness of the musical settings by even lesser known seventeenth-century Spanish composers. A prolific writer by any standard, Lope de Vega astonishingly produced some 1,800 plays, most of them comedias, and his poetry inspired the flowering of the canción. It is hardly surprising then that one of his texts served as the libretto for Cosimo Lotti’s La selva sin amor, the first opera to be performed in Spain (1629). Those included on this disc reveal sharpness of mind, a deep sense of honour, passion and frank sensuality—qualities that inspired composers such as Mateo Romero, Manuel Machado, Francisco Guerrero, Juan Blas de Castro and José Marin. • The poised passion, delicacy of tone, intonation - elegant diction of the soprano Montserrat Figueras, in concert with the imaginative artistry and native intuition of Jordi Savall (in the dual role of continuo viol player extraordinaire and director of a specially augmented Hespèrion XX), bring texts and music to life. Because little of this music is readily available, the degree to which Savall has departed or interpreted the scores is difficult to assess. Certainly, these are very appealing and colourful performances, sure to excite interest amongst intrepid baroque music lovers, but it seems important to point out that, by the lavishness of their instrumentation, they may in fact represent idealized versions. The listener’s attention is never allowed to wander: single selections are introduced by percussion, strings and wind instruments, followed by vocal phrases variously accompanied simply by plucked continuo and combinations of wind or strings, which alternate with instrumental interludes. • When in Blas de Castro’s Desde las torres del alma, Figueras calls “wake up”, her demand is punctuated by cornett, guitar and percussion. But perhaps the most dramatically effective moments come in the section accompanied only by Savall himself (who is, incidentally, married to Figueras) and the a cappella passages in Romero’s Caiase de un espino (which addresses illusion and disillusion) and Guerrero’s powerfully declaimed passage in Si tus penas (from his Soliloquios amorosos de un alma a Dios). The cumulative effect of this kaleidoscopic approach—very theatrical in its way—will for some be aurally intoxicating. This impression is doubtlessly enhanced by the presence of a series ol battle pieces interspersed throughout the disc, in which the juxtaposition of musical forces successfully conjures up the unseen drama. The percussion effects, in particular, are superb, though I found some of those in Sebastián Aguilera de Heredia’s Ensalada a little too alarming. The cornett solo and the dulcian timbres contributed delightfully to Juan Cabanilles’s Tiento Ileno, while the solitary viol consort version of his Passacalles V provides a much needed foil to so much instrumental colour. This delightful introduction to Spanish baroque dramatic music, superbly performed with great panache and style, is warmly recommended, and I hope it will be followed with recordings of more extended musical dramatic works.

• anon.: No hay que decirle el primor

• Arauxo: Batalla de Morales

• Cabezón, A: La Dama le demanda

• Cabezón, A: Tiento III

• Castro, Juan de: Desde las torres del alma

• Castro, Juan de: Entre dos álamos verdes

• Guerrero, Francisco: Glosas sobre Hermosa Catalina

• Heredia, S: Ensalada

• Heredia, S: Tiento de Batalla

• Machado, M: Afuera, afuera que sale

• Machado, M: Que bien siente Galatea

• Morata: Aquí me declaró su pensamiento

• Ortiz, D: Passamezzo moderno III

• Ortiz, D: Romanesca VII

• Romero, M: Caíase de un espino

• Valderrabano: Soneti VIII, XIII

• Vasquez, J: De los álamos vengo, madre

• Vega, F: Como retumban los remos

• Vega, F: De pechos sobre una torre

• Vega, F: En tanto que de rosa

• Vega, F: Si tus penas no pruevo

Works: • anon.: Corten espadas afiladas

• anon.: No hay que decirle el primor

• Arauxo: Batalla de Morales

• Cabezón, A: La Dama le demanda

• Cabezón, A: Tiento III

• Castro, Juan de: Desde las torres del alma

• Castro, Juan de: Entre dos álamos verdes

• Guerrero, Francisco: Glosas sobre Hermosa Catalina

• Heredia, S: Ensalada

• Heredia, S: Tiento de Batalla

• Machado, M: Afuera, afuera que sale

• Machado, M: Que bien siente Galatea

• Morata: Aquí me declaró su pensamiento

• Ortiz, D: Passamezzo moderno III

• Ortiz, D: Romanesca VII

• Romero, M: Caíase de un espino

• Valderrabano: Soneti VIII, XIII

• Vasquez, J: De los álamos vengo, madre

• Vega, F: Como retumban los remos

• Vega, F: De pechos sobre una torre

• Vega, F: En tanto que de rosa

• Vega, F: Si tus penas no pruevo

nośnik

SACD

gatunek

Muzyka klasyczna

producent

Alia Vox

data wydania

01-12-2007

EAN / kod kreskowy

7619986398310

(Produkt nie został jeszcze oceniony)

cena 85,00 zł

lubProdukt dostepny w niewielkiej ilości.

Wysyłka w ciągu 3 dni roboczych

Darmowa wysyłka dla zamówień powyżej 300 zł!

Darmowy kurier dla zamówień powyżej 500 zł!

sprawdź koszty wysyłki