kompozytor

Desyatnikov, Leonid

tytuł

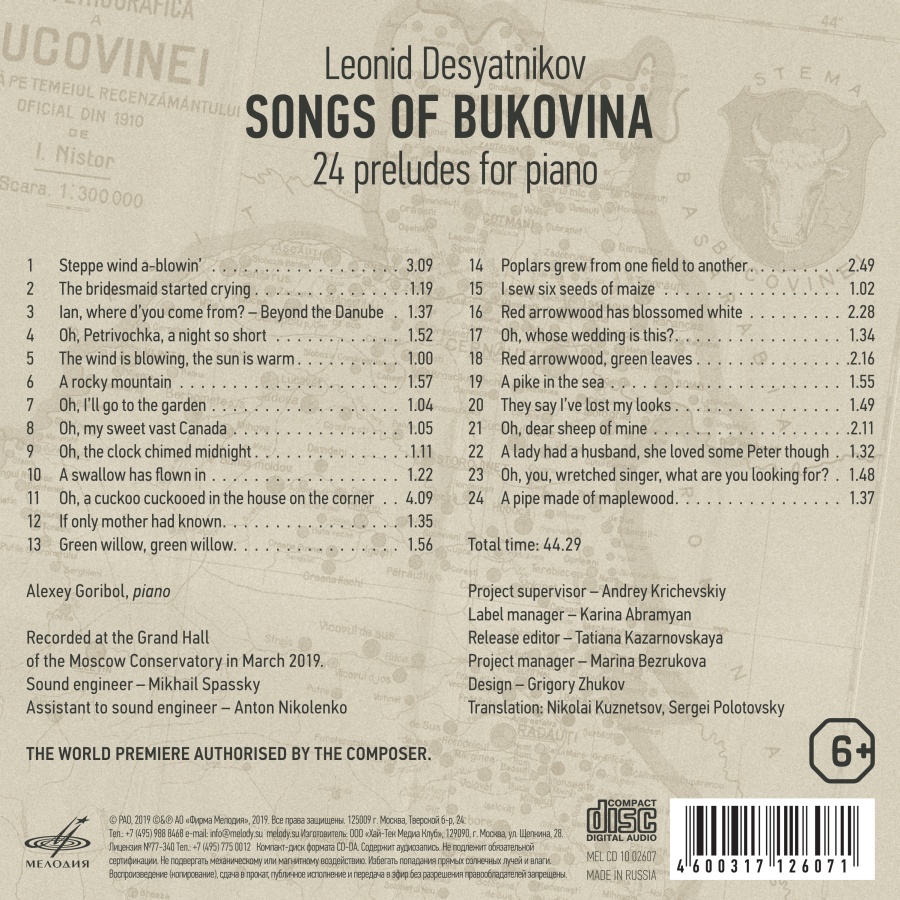

Desyatnikov: Songs of Bukovina

wykonawcy

Goribol, Alexey

nr katalogowy

MEL CD 10 02607

opis

Melodiya presents a world premiere, the recording of Leonid Desyatnikov’s Songs of Bukovina performed by Alexey Goribol, a dedicatee of the cycle. The liner notes were written by Maria Stepanova, the author of In Memory of Memory. • Leonid Desyatnikov is one of the most ‘textual’ composers of our time. However, in his latest chamber opus, Songs of Bukovina, he chooses the format of ... ‘24 Preludes for Piano’! This is how the cycle is subtitled. The tradition originated by Bach, adapted by romanticism into the microcosm of ‘cycle of miniatures’, and elevated to the rank of ‘intimate diary of the artist’ by hyper-individualists like Chopin, Scriabin, et al. is crossbred by Desyatnikov with Transcarpathian folklore. The music of the Bukovinian prelude songs” combines the intonation spice of West Ukrainian flavors with devices from the arsenal of today’s composing techniques. • This music was performed for the first time in October 2017 in American Ballet Theatre’s production choreographed by Alexei Ratmansky. The ballet included a half of twenty-four preludes. The premiere of the entire cycle performed by Alexey Goribol took place in Perm in June 2018. The Songs of Bukovina were premiered in Moscow on October 1. It was after the Moscow premiere when it was agreed that the Songs of Bukovina would be recorded by Firma Melodiya. Leonid Desyatnikov was present at the recording sessions, and the final result received a high appraisal from him. • The creative work of Leonid Desyatnikov, one of the most soughtafter Russian composers of today, is difficult to make fit any existing framework. He cannot be labeled as a dissident avant-gardist, or as a Soviet conformist, or as a neo-folklorist. In the age when a composer’s main problem lies in the antinomy of ‘original’ and ‘borrowed’, the author of The Children of Rosenthal, an opera about cloned classical composers, makes ‘unoriginal’ into the main creative principle (“The more it changes, the more it stays the same”). The composer simply eliminates the opposition of ‘one’s vs. someone else’s.’ However, this is far from being identical to Stravinsky’s neoclassicism with its almost Salierian attitude to composition (“I cut up music like a corpse”); on the contrary, Desyatnikov sincerely believes in the selected quotations and allusions, which gives the listeners salutary sound and semantic ‘beacon lights’ in the murky streams of the modern academic discordance.

nośnik

CD

gatunek

Muzyka klasyczna

producent

Melodia

data wydania

04-11-2019

EAN / kod kreskowy

4600317126071

(Produkt nie został jeszcze oceniony)

cena 79,00 zł

lubProdukt na zamówienie

Wysyłka ustalana indywidualnie.

Darmowa wysyłka dla zamówień powyżej 300 zł!

Darmowy kurier dla zamówień powyżej 500 zł!

sprawdź koszty wysyłki